올해 필자는 처음으로 칸영화제에 갔다. 경쟁부문에 한국영화가 두편이나 오른 이번 영화제에 한국영화 팬들은 볼거리가 많았다. 크로아제트 거리에는 <올드보이>의 대형 포스터가 걸렸고 홍상수 감독의 이름이 표지에 실린 <카이에 뒤 시네마>가 쌓여 있었다.

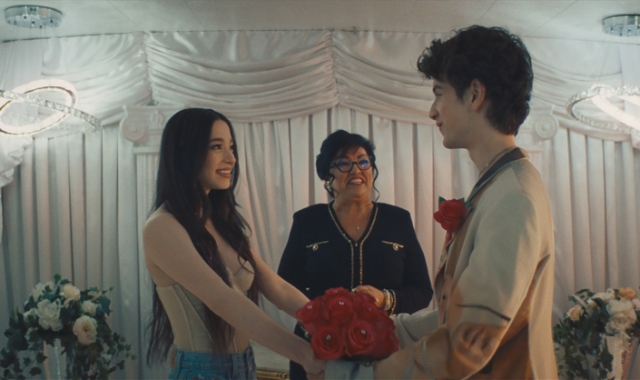

주 경쟁부문에 대조적인 스타일을 가진 한국영화 두편이 진출한 것이 특히 좋다고 생각됐다. 일반 관객들은 <올드보이>에 강한 반응을 나타낸 반면, 많은 전문- 특히 프랑스- 평론가들은 냉담한 반응이었다(이 영화의 상영회는 한국영화를 처음 접하는 많은 관객에게 가장 기억에 남는 한국영화의 첫인상은 폭력 묘사라는 사실을 다시금 입증해주기도 했다. 필자는 <올드보이>뿐만 아니라 가벼운 코미디를 대했을 때도 외국인들의 이런 반응을 자주 보았다).

반면, 홍상수 감독의 영화는 평론가들(특히 프랑스 평론가들)의 환영을 받았으나 일부 관람객에게 혼란스러움을 남기기도 했다. 그러나 전체적인 반응은 두 영화 모두 화젯거리를 던져준다는 것, 그리고 한국이 혁신적이면서도 완성도 높은 영화의 중요한 원천임을 보여주었다는 것이었다. 이 두 영화를 모두 아끼는 필자로서는 받아 마땅한 주목을 받는 것을 지켜보는 일이 흥미진진했다.

그러나 필자가 칸에 가게 된 것은 영화관람이 아니라 일을 하기 위함이었고, 그 일은 <스크린 인터내셔널>을 위해 한국영화와 일본영화에 대해 취재하는 것이었다. 여러 영화사를 대하면서 한국영화가 사업 면에서 다른 나라와 어떤 방식으로 교류하고 있는가에 대한 감을 키울 수 있었다.

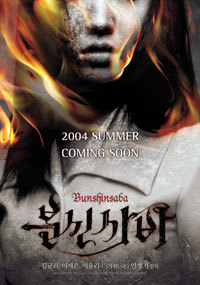

한 가지 눈에 띈 점은 일부 한국 영화인들은 이제 한국의 투자 없이도 영화를 제작할 수 있을 정도로 해외에서 인정받고 있다는 사실이다. 안병기 감독의 <분신사바>(사진)는 일본에 단 한 차례 팔린 것으로 전체 제작비를 충당할 수 있을 정도였다. 김기덕 감독 또한 차기작을 한국 자본 없이 만들 계획인데, 성공할 것으로 기대된다. 대부분 이런 것은 일본 덕을 보는 경우가 많은데, 가깝고도 거대한 시장을 가진 일본은 한국에 엄청난 이점을 제공한다.

일본 영화사들과 얘기하면서 필자는 다른 각도에서 이런 사례들을 볼 수 있게 됐다. 어떤 면에서 한국영화의 상업적인 성공은 일본 내에서 변화를 가져오기도 했다. 일본 정부는 수년 동안 자국 영화산업을 외면하다가 이제 그 진흥에 훨씬 적극적으로 나서기 시작했다. 그러나 필자가 접한 일부 일본 제작자들은 한국 문화시장이 여전히 완전개방되지 않았다는 점에 답답해했다. 한국에서는 극장개봉을 거친 일본영화만이 DVD로 출시될 수 있다. 한국의 불균형적인 배급체계로 인해 일본영화들은- 1950년대와 1960년대 고전을 포함해서- DVD로 나오기 매우 힘든 실정이다. 방송제한으로 일본 스타들이 널리 알려지는 것 역시 힘들다. 일본에서는 TV를 통해 배용준이 일약 대스타가 되었지만 한국에서는 여러 가지 제약으로 일본 스타들이 알려지는 것이 어렵다.

2005년 한국은 일본 대중문화를 완전개방할 가능성이 있다. 일본이 현재 한국 영화산업에 여러 가지로 이바지하고 있다는 점을 고려할 때, 이는 적절한 조처가 될 것이다.

- Korea, Japan, and the rest of the world at Cannes -

This year was my first-ever trip to the Cannes film festival, and with two Korean films in competition there was much of interest for fans of Korean cinema to see. The Croisette was adorned with a big poster of Old Boy, while stacks of Cahiers du Cinema featured Hong Sang-soo's name on the cover.

I thought it was especially nice that Korea had two films of such contrasting styles in the main competition. Old Boy got a strong response from the general audience, but was coldly received by many professional -- especially French -- critics. (The film's screening also reinforced the fact that for many first-time viewers, Korean cinema's portrayals of violence leave the most memorable first impression. Not only in Old Boy: I've seen this in foreigners' reactions to lighthearted comedies as well)

Hong Sang-soo's film, in contrast, was warmly embraced by many critics (especially the French), but did leave some viewers feeling confused. In general, however, there was a sense that both movies provoked discussion and demonstrated how Korea is an important source of groundbreaking, accomplished cinema. For me, who adores both of these movies, it was a thrill to see them get well-deserved exposure.

However I went to Cannes not to watch movies, but to work -- my job was to report on Korean and Japanese cinema for Screen International. Talking to different companies also gave me a sense of how Korean cinema interacts with other countries in a business sense.

One thing that struck me is that some Korean filmmakers have now become respected enough abroad that they can make films without any financial support from Korea. Ahn Byung-ki's Bunshinsaba earned enough from a single sale to Japan to pay for the entire film's budget. Kim Ki-duk also hopes to make his next film without any Korean money, and I expect he will be successful. Mostly this is thanks to Japan -- its huge market, so close by, is a tremendous advantage for Korean cinema.

In talking to Japanese film companies I could hear another side to the story. In some ways, the commercial success of Korean cinema has inspired change. The Japanese government is now becoming more aggressive about promoting its film industry, after years of ignoring it. However some Japanese producers I spoke to felt frustrated that Korea's culture markets were still not fully open. In Korea, Japanese films can only be released on DVD after a theatrical release. Korea's unbalanced distribution system ends up making it very difficult for Japanese films -- including classics from the 1950s and 1960s – to appear on DVD. Restrictions on TV also make it hard for Japanese stars to become well-known. Bae Yong-joon became a tremendous star in Japan through TV, but restrictions make it difficult for Japanese stars to gain the slightest recognition in Korea.

Korea may fully open its market to Japanese pop culture in 2005. Given the many benefits that Japan now brings to the Korean film industry, it will be an appropriate gesture.